Whats A Shoulder Turn? Part 3

- by Kelvin Miyahira

Since I covered the shoulder turn on the backswing for the last two months, I need to finish this subject by detailing the shoulder movements on the downswing. This should be very simple to do since the movements aren’t really coming from the shoulders. The movements in a great golf swing are still coming from the spine, rib cage and associated muscles.

Thus, while everyone is using the shoulders as markers, it should NOT give one the impression that they are the prime movers in the downswing. So let’s take a closer look at some puzzling or less than optimal notions about the downswing shoulder movements and finish off with what is truly the best move you can make.

Biomechanics Blurriness

Jim McLean’s biomechanical findings may have rung true many years ago. But since 1997 and the emergence of the Great Once (Tiger Woods), the golfing world has seen a change in the image of what a great golf swing looks like. Just look at the best young golfers from around the world and you see that they grew up watching Tiger Woods. Ryo Ishikawa, Anthony Kim, Jhonattan Vegas, Danny Lee, Matteo Manassero, Rory McIlroy, Seung-Yul Noh, Rickie Fowler, Martin Kaymer, Alvaro Quiros and other young golfers have had the images of Tiger burned into their minds from a young age.

So back to McLean’s X-Factor. His first article was about the differential between shoulder and hip turn. The higher the separation between these two segments, the better. Then X-Factor Stretch was about increasing the X-Factor during transition. And last, X-Factor 2 was about closing the gap between the shoulders and the hips at impact. The first two are still valid today, however, it is the latter that has changed since Tiger roared on the scene.

How the swing has changed?

Here’s a top view of current world #1 LPGA golfer Yani Tseng vs. Karrie Webb. No doubt Karrie is a Hall of Famer and still one of the top players. But you can see the difference between old school Karrie swing and the Tiger-influenced modern swing in Yani. Her shoulders have not passed her hips and this is just after impact. Whereas, Karrie’s shoulders have clearly caught up to her hips. Thus in the old school swing, you can imagine the shoulders and the upper torso playing a huge role.

Here’s Jeev Milkha Singh showing the shoulders catching up to the hips. Remember he had quite an open clubface at the top thus a lower body stall is necessary to allow time for the hands to flip/roll the clubface square.

From front view, here’s a former great junior golfer turned struggling LPGA pro Aree Song. After making a big splash by placing 10th at the US Women’s Open at the young age of 13, she slowly eroded her golf swing by drinking the Kool-Aid and turning a once dynamic swing into this...

You can see how Aree closed the gap between shoulders and hips at impact. But is this how the PGA tour guys are swinging these days? Do you see them decelerate the lower body like this or like many do on the LPGA tour? Don’t think so.

So what’s different?

Tiger used to have the most dynamic lower body movements since young Jack Nicklaus in the early 1960’s. His legs and hips would continue to rotate past impact before decelerating or braking. In other words, the entire spine was rotating at impact and while there may have been some closing of the gap there’s no way he did it intentionally or consciously.

Take a look at former #1 golfer in the world Lee Westwood. He looks great at this point. But some people believe (and maybe they’ve trained him) that the legs and hips have done their job by this point in the swing and that the transfer of energy should begin here.

One can clearly see how early he’s firing his right shoulder and hands. He’s a tremendous athlete but maybe he has been trained out of his athleticism?

Biomechanical Chicken or the Egg Question

Does anyone realize that the segment interaction principle (and the kinetic/kinematic chain) has not been agreed upon by all biomechanical scientists? In other words, instead of the proximal segments (legs, hips and torso) transferring energy to the distal segments (arms/hands/clubhead) by accelerating then decelerating in a sequence from ground up.

There are some biomechanical scientists who have come up with the exact OPPOSITE conclusion!!! Read this important quote from Duane Knudson’s Fundamentals of Biomechanics.

“There are some scholars who have derived equations that support the proximal-to-distal transfer of energy (Hong, Cheung, & Roberts, 2000; Roberts, 1991), while others show that the acceleration of the distal segment causes slowing of the proximal segment (Putnam, 1991, 1993; Sorensen, Zacho, Simonsen, Dyhre-Poulsen, & Klausen, 1996).”

In other words, when an ice skater that is spinning fast extends his/her arms out, they begin to slow down. If that makes sense to you, then could it be that in a golf swing where the body is rotating fast (and working to remain rotating!) and the arms/club are extended out that it will cause deceleration of the body? The key point is that there is no conscious attempt to decelerate any part of the body!!!

Yet, in practical application of biomechanical principles these days, active braking and deceleration is all that is taught or trained.

Even Dr. Rob Neal concedes this point in Brian Manzella’s Anti-Summit but who understands the implications?

Another important point that I have found is that there are ZERO bowed drive/holders (from my release styles article) that are slowing down their bodies.

The effect of a sudden braking of the lower body (or what I have called a stall or outright stopping of the body) is going to create a flip, a roll or a flip/roll release. It might create more clubhead speed at the end but you’ll also sacrifice accuracy. This part is not rocket science. If you want a stable, driving hand position through impact, the rotational movement of the body is an absolute requirement.

Thus, there are important questions that need to be asked of the biomechanical experts that are training golf instructors to teach others how to swing a club. If there is no consensus amongst the scientists that research this phenomenon, how can virtually every biomechanist in this country (from other countries as well) that is involved in golf (or baseball, tennis or any other sport), choose the same side in this argument, not risk being totally wrong and potentially ruining the players they are working with?

The movement of the lower body is going to be covered in the next few articles. Can you see the flip? Y.E Yang 2009 PGA Champion and Tiger beater is a tremendous competitor with a lot of athleticism. But I’ll bet he’s been trained to brake the left leg.

Can you see the left foot trying to remain quiet or stop? Can you see the stall? Of course this transfers the energy and speed through to his hands. But does this represent the best one can do? The stall and the flip are like peanut butter and jelly. The peanut butter is legs/feet sticking to the ground and the jelly are what your hands turn into.

For instructors, how sure are you that these biomechanists are right? When you get the perfect kinetic/kinematic chain graphs from your student, does it look like a great golf swing or do you blindly trust the graphs? We already know the biomechanists do not like to look at videos and would rather see the graphs. Still want to put blind faith in this?

Implications for Segment Interaction Believers

If you believe in segment interaction and the kinetic/kinematic chain, then there are implications in the way you train and ultimately in the way you are trained to swing. Here are some of the more recent ways the Kool-Aiders explain this:

“Summation of forces at impact requires braking your lower body to let the energy transfer to the shoulders and then out to the arms and clubhead.”

“To create the perfect kinetic/kinematic chain graphs requires DECELERATION.”

“Pushing against the ground, gripping the ground with your toes creates more power.”

This one is from Sean Foley, “you can’t fire a canon from a canoe.” But you can fire a canon from a ship can’t you?

Looks like Foley has a little flip and lower body stall in this swing. Just so you know, Foley’s biomechanical guru is Chris Welch (non-golfer) and he’s is a major proponent of the segment interaction theory/kinetic chain. Of course his “knowledge” is being passed on to Tiger.

This is from the Accenture Match Play 2011, where Tiger gets eliminated in the first round. Insanity? The inability to say, “I’m sorry”? What else could explain why Tiger would change to this?

Undecided?

If you’re undecided about this read on.

Here’s the European Bubba, Alvaro Quiros moving like Tiger at his peak.

Side Note: If you watch his movements carefully the power comes from the spine and pelvis, not his legs or shoulders. He’s using a float/rotating left leg that facilitates more spine/hip rotation through impact. Suffice to say, it isn’t what Tiger is doing these days. Tiger is “gripping the ground with his toes” now.

Just looking at the top 64 players in the world at the Accenture Match Play last week, there’s just a handful of players (including Tiger and Paddy) buying into the “brake to speed up” theory. No doubt, they have drunk the Kool-Aid. The rest are moving well through impact and I will put some videos up on youtube so you can see for yourself. Also, the next few articles will cover the hugely important lower body action. I will detail the downswing movements of the lower body so that you can float/rotate through impact vs. braking prior to impact. This will connect the dots between how the hands move through impact as well since this is how we can maximize accuracy while not giving up distance.

But I digress; let’s get back to the shoulder movements and how they should be working.

Some Physics: Force Coupling

Before I lay the groundwork for the way the body moves in great golf swings, let’s try to get a theoretical framework for this from physics.

While many people believe in the legs, hips and shoulders driving the swing, I believe it is the spine, the dorsal muscles associated with the spine and the pelvis that are doing the work. Of course the leg muscles are assisting but not in the way everyone thinks. Since we know enough of what everyone else thinks, let’s skip that and on to a different point of view.

Is it possible that muscles can apply force to both sides of the spine and create torque or rotational force? In physics, this is called a force coupling. Simple definition from Answers.com:

“Two equal, but oppositely directed forces acting simultaneously on opposite sides of an axis of rotation. Since the translatory forces (forces that produce linear motion) cancel out each other, a force couple produces torque (rotatory forces) only. The magnitude of the force couple is the sum of the products of each force and its moment arm.”

Since I fell asleep in physics class (it was right after lunch) we can skip the mathematical calculations and just get the gist of what this is all about. What this really means is that there is a potential for the golfer to swing his/her body like a revolving door instead of a hinged door (posting solidly on the left side).

Also, if you think about it, when running, isn’t this the same way your body moves? It is not hard to understand that humans were made for this type of locomotion and it’s best to use that to your innate advantage versus trying to invent a new way to run like a robot.

Where does the movement come from?

To understand the true power source, let’s look at the powerful swing of Dustin Johnson from a semi-top view.

Notice from this top view of Dustin Johnson, we can see the shoulders. The first picture shows the estimated angles of his hips and shoulders about halfway down. By impact the shoulders have closed somewhat but can you see how much of the X-Factor still exists?

The old biomechanical model (Nick Faldo era) from 10 to 20 years ago, found the shoulders catching up to within 10 and 20 degrees of where the hips were at impact. This does not look anywhere near just a 20 degree separation of the shoulders at impact.

Do Graeme McDowell’s shoulders look like they’re catching up?

Here’s another great image to dispel the notion of the shoulders catching up. Graeme McDowell’s shoulders look close to square while his hips are wide open at impact.

Notice the red line is his approximate lumbar spine position halfway down. But by impact, the lumbar spine has rotated plus extended (moved to a more vertical position) while lateral bending has increased (see the dotted green lines showing the bending of the spine toward the ball).

So what’s really going on?

Lateral bending changes shoulder tilt axis

We’re so used to seeing the correct movements of a tour level golfer that perhaps seeing a poor golfer like Rush Limbaugh might help you to get a contrasting image.

While we all can recognize that he’s standing up or extending his spine through impact, stalling his lower body and his shoulders have closed the gap on his hips, the key is that he has no lateral bend. The lack of lateral bend causes a disconnection between the upper and lower halves of the body thereby allowing the shoulders a chance to catch up to the hips.

But if correctly done, the shoulders should turn on a far more tilted angle than the hips. This means the shoulders can be moving faster than the hips but since they will have more of a vertical orientation in the rotation, positionally, they won’t catch up.

Here’s Chris Tidland from the Justin Timberlake Classic showing what it looks like to have your shoulders catch up to the hips in a tour player. Can you see the lack of lateral bending in his spine?

Now can you see the difference? G-Mac’s shoulders are turning on a far more vertical plane with lateral bending and his hips have rotated far more.

If you believe the shoulders should try to catch up to the hips, the likely result is the entire lower body stalling with the obliques and arms driving the motion from halfway down on the downswing through impact.

If the shoulders aren’t causing movement, what’s moving?

To get into the position that G-Mac is in at impact, your spine muscles need to move.

The muscles are capable of rotating and extending the lumbar spine. You’ll see that they are the spine engine muscles, namely the multifidus, iliocostalis lumborum, and the longissimus lumborum.

Muscles rotating and extending the lower thoracic spine are the iliocostalis thoracis, spinalis thoracis, semispinalis thoracis, longissimus thoracis, and the rotatores thoracis.

Lateral bending is aided by latissimus dorsi, quadratus lumborum, psoas major, intertranversii lateralis, iliocostalis lumborum and the longissimus lumborum.

You don’t need to know all these muscle names in order to execute these movements but you do need to know that these muscles need to be trained for this movement.

Current biomechanical methods

DJ top view imagine sensors

Another problem that needs to be addressed by the biomechanical experts is the placement of one sensor (red circle) near the top of the spine that supposedly marks where the shoulders are. In the first picture, the sensor can be calibrated to be parallel to the imaginary shoulder line (which is only constant at address since the clavicles move independently during the swing). But on the right, would you say the sensor is aligned in the same way with the shoulders?

With right side lateral bend, left rib cage/spine bending and both shoulders protracted, this “deforms” the thoracic spine in such a way that the sensor no longer is parallel with the variable shoulder line (see green circle and line).

Review of Transition Right Side Movements

Remember that during transition, there is external rotation of the right shoulder along with the scapula’s retraction. This forms the “elbow move” that I wrote about in a previous article. Just as a baseball pitcher drives the elbow forward before accelerating the hand/ball, great golf swings use this power source too.

Watch how fast his right elbow drops into the slot in transition and early downswing. Paired with what I had called the “stop sign move” which is comprised of right shoulder external rotation, right forearm pronation and right wrist extension, this loads the right side and creates proper “lag.”

On another note, the maybe ambiguous term “lag” should be replaced by a more anatomically correct description of the actual movements. In other words, if one has lag (ambiguous type) but supinates the right forearm and adds more left arm internal rotation, what does that do?

See the Rod Pampling’s vs. Sergio Garcia’s position? What’s the point of having a lot of lag if you cup the left wrist (extend) instead of bowing (flexion), add more left shoulder internal rotation on the downswing like Sergio? It will overly flatten the downswing plane and leave the hands/wrists/clubface in too open a position. From this point, it is hard for anyone, even for someone as talented as Sergio to square it without having to flip/roll it.

Sergio has been the poster child for anti-lag sentiment. Because he had such great lag and has not lived up to the hype, people are afraid of holding onto lag. But he never did his lag correctly nor was ever taught how to square the clubface without flipping, therefore the problem isn’t lag, it’s a problem of poor instruction.

Other “Shoulder Turn” Movements

Left Scapula Movement

The left scapula movement is pretty simple. It is protracted on the backswing and stays protracted on the downswing until well after impact. There is an increase in the amount of protraction during the downswing as the spine muscles rotate the spine away from the scapula.

Here’s Luke Donald from just prior to impact. The left scapula is stabilizing the left arm for impact while the spine is still driving the swing.

Watch this great view of the Rickie Fowler’s spine/rib cage moving while the left scapula remains protracted until well after impact. I’ve pointed a red arrow at the left scapula as it begins to retract and “turn the shoulders” as the spine reaches the end of its rotation and begins to stall. If you look carefully, you can even see his rib cage bulging and stretched out at impact.

Contrast that with many amateurs that don’t rotate well before impact and have a lot of rotational energy AFTER the ball has been struck.

Right Scapula Movement

Here’s Bubba Watson. You can see the firing of his rear shoulder or scapula protraction is just before impact. Thus, if there is any closing of the gap, this would be the mechanism but this occurs about .02 seconds before impact.

Here’s the massive back of Rafael Nadal executing a serve. Notice the rear scapula protracting just prior to contact. This is a powerful move that involves your pectoral and serratus muscles.

Too Early?

Here’s Anthony Kim from a front top view.

The red lines show how lateral bend and the rotator cuff muscles hold the right scapula in retraction at the start of the downswing. By the middle of the backswing you can see the green lines appear to move faster at the shoulder joint than the neck area. This would show the area where protraction is occurring. Since I forwarded the video the same amount of frames per line drawn, the protraction occurs just after the halfway point of his downswing. But AK’s protraction might be a bit early. Perhaps he’s a victim of the influence of modern biomechanics? His coach Adam Schriber is also a disciple of Welch.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evR7X4oXnTY

If you look at AK in this video, he certainly isn’t moving like he used to.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uETk4gtTTXk

Maybe we’ll just have to copy Bubba since we know Bubba doesn’t listen to instruction nor biomechanics.

Combo Micro Moves of the Right Side

The previously mentioned moves set up the next few moves. As the right scapula begins to protract, it will start the right arm extending as well. But a couple of micro moves occur along with the right arm extension that are critical because without it, flipping will occur.

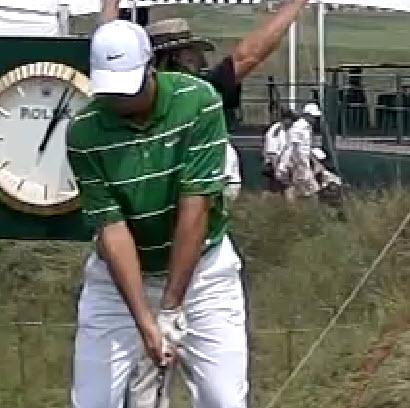

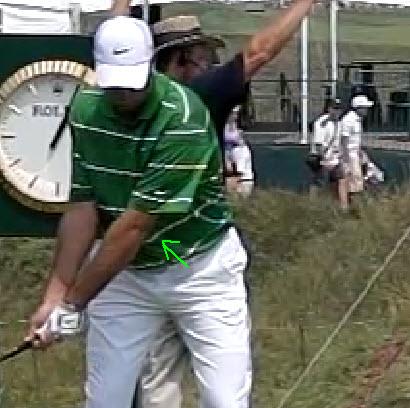

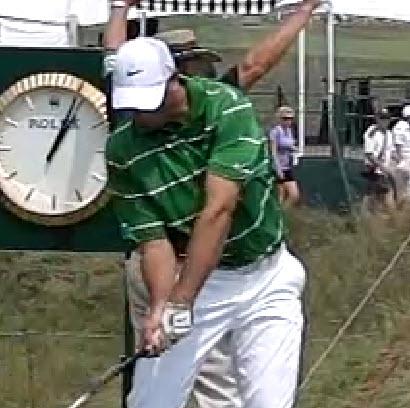

Here’s a good view of Tiger doing these moves. Right shoulder internal rotation begins to occur after the right arm has extended about halfway.

Also, the right forearm should continue to pronate up until just a few frames prior to impact.

The rest of the hand/arm movements have been covered by my earlier article on Tiger’s release so I won’t get into that.

Left Shoulder Internal Rotation

The left shoulder internally rotates on the backswing as said in the previous article. But what does it do from there? If you’re Hank Haney, you believe the left shoulder does the opposite on the downswing and far earlier than it should. In other words, the left shoulder externally rotates to put the club back “on plane” for the downswing. We have seen Tiger do these types of practice swings before under Haney’s watch. It looks like he’s laying off the club then rotating the left arm (pronating) exaggeratedly on the backswing and then externally rotating the shoulder early in the downswing and supinating the left arm to bring the club down in front of him.

But is there another way?

Take a look at Tiger before Haney. His left shoulder remained internally rotated.

Notice the left elbow position at the address position of Stewart Cink. As the left shoulder internally rotates, the elbow rotates along with it. But in the 3rd picture that is just prior to impact, the left elbow is pointed farther right than at address.

At impact, it is still pointed farther right than at address. It is only post-impact that the left shoulder external rotation occurs. But Cink could be even better if he externally rotated his left shoulder even later.

Here’s Steve Marino with a great impact position and very stable arms/clubface through impact. This guy should be winning tournaments! If you’ll notice, I’ve pointed out the logo on his left sleeve to mark the rotation of his humerus which shows where the bulk of the external rotation occurs late in his follow through.

The importance of the left shoulder trying to remain internally rotated at impact has the effect of stabilizing the shoulder/arm’s position (along with the left scapula) while at the same time needing to have more supination of the left forearm to square the clubface.

This brings up an important point. Some people ask why the left forearm supination and left wrist flexion should be exaggerated in doing the Impact Snap Device exercise. This would be part of the reason.

Also, lateral bending, holding lag and continued rotation of the body will leave the clubface more open as well. Thus, the amount of supination needed to square the clubface is far greater than for a poor swing.

Or you can choose to use left shoulder external rotation as part of your release style, but this automatically rotates the entire left arm and leaves it in a more unstable, weaker position (shall we say it encourages a flip/rolling release?). This means the left forearm can supinate faster too and that means hooks.

Traditional Flip/roll release

Here’s another player from the Justin Timberlake classic showing what we were all taught 40 years ago. Can you see the external rotation of the shoulder causing the entire arm to rotate? This allows faster supination but then in order to try to slow the clubface rotation, he slightly flips under by extending the left wrist(opposite of bowing or flexion) at impact.

This is part of the flip/roll release that is the most difficult way to play golf. Timing must be perfect. Your body must slide a little extra toward the target to avoid hitting fat shots and hit a thousand balls a day to get the timing right.

Left Arm Straight?

Here’s Trevor Immelman showing a great bowed drive/holding release. But his left arm is not straight at impact.

Contrary to popular belief, this is correct. Once again the left arm/wrist is in a stronger, more stable position when it is slightly bent (plus held with internal rotation and scapula protraction) vs. being straight. Notice both arms straighten well after impact.

Another important point, isn’t Trevor’s large shaft lean alone and great body rotation enough to insure that the bottom of his swing is in front of the ball???

So many golfers have this odd notion that in order to get the bottom of their swing in front of the ball it requires the body to slide toward the target excessively. Whether it is the chest/upper body lunging forward or the lower body sliding to move the entire body toward the target, doesn’t it seem like a Band-Aid fix for casting or early releasing and possibly flipping?

Here’s Steve Stricker with a flat DH’er release showing the same bent left arm.

And Matt Kuchar has a knife edge DH’er release style with a slightly bent left arm.

Some people can even hyper-extend the arm but it is even weaker in that position and will cause faster supination (this means hooking).

When should the Right Arm Straighten?

Here’s a picture of Hunter Mahan straightening his right arm early during a practice swing. Seems a bit early to extend the right arm. Just as the ice skater spinning extends the arms to slow down, this might contribute to an early stall of the body which in turn causes and earlier release of the wrists (shall we say increasing the chance of flipping?). Only Hunter’s tremendous talent allows him to fight off the stall and flip.

Instead, Camilo is firing his right bicep and forearm extensors to retain the lag.

Tiger does the same.

Bubba knows how to lag and extend the right arm late. Bubba also knows how to lead the tour in driving distance and greens in regulation!

Thus, the rehearsals that Hunter does actually help to myelinate this motion of releasing his right arm early. Only his tremendous athletic ability allows him to avoid flipping it at impact.

Great Players Overcome

Here’s Justin Rose doing the same early right arm release since he also is a student of Sean Bieber Foley.

But Justin is not able to get into the same impact position as Hunter and appears very close to flip/rolling it. Certainly it is not as stable an impact position as Hunter. But it just goes to show you that talent can overcome questionable instruction.

Left Arm Connection to Chest

Rory Sabbatini shows an extreme disconnection between the left arm and the chest at impact. This helps to stabilize the left shoulder/arm complex for impact. As you can see, he’s got the same left shoulder held in internal rotation while driving the bowed left wrist. No wonder he plays well in the wind.

Thus, while many are interested in retaining connection or pressure point, it may serve to prematurely externally rotate the left shoulder along with the rib cage/spine rotation thereby destabilizing the shoulder/arm/wrist for impact.

Is there a difference in the release style between retaining left arm pressure or connection to the chest vs. disconnecting?

Hopefully this sheds some light on how the best players in the world are using their “shoulders.” Unfortunately, many still believe that it is the shoulders that are rotating (in the traditional sense) when they really aren’t. They are going along for the ride that the spine engine is supplying and if they add anything other than stability, it would be (or should be) just milliseconds before impact.

Next month’s article on how the hips work should be very eye-opening.

Power Bands

Ido Portaldo from youtube doing the scapula exercises in “What’s a Shoulder Turn part 2” recommended Iron Woody Power Bands to train the muscles. But I have found that they are incredibly good for training the spine and hip muscles as well. These come in several different sizes. An average man should probably use Iron Woody #3 and if above average strength use #4. Women and juniors can use a #2. They can be found on ebay. Later, I’ll post some videos on how to use them.

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n0t0VLanxFo

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Fq9ZwgNYLY

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DpxRLOl3vzg

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jEm4AmkfxzE

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FA1umE7C_eA

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EMqtEyDQ99o

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-vwhX96VDxY

- http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u3jGPqe3ctk