How To Shift Your Weight Without Sliding

- by Kelvin Miyahira

In baseball there’s a long-running debate on whether the swing is rotational or linear. In golf we appear to be headed in that direction as well. But the answer is obvious; there are rotational as well as linear elements in the golf swing. The question seems to be which of the two is emphasized most. I am on the side of emphasizing rotation (because the guys with great swings have excellent rotation) while most of golf instruction is on the side of stressing the linear (lateral) motion whether they realize it or not.

From the biomechanical perspective, the science is seemingly into rotational movements but with a twist (or shall we say deceleration?). In promoting the kinetic/kinematic chain (rotational movement measured in degrees per second), they are at the very least de-emphasizing linear movement. They can list the linear movements later but most of the emphasis is of rotational movements.

So that’s the challenge. Here’s a grey area in the world of golf instruction that hasn’t been parsed out critically. We know that a weight shift (linear movement) is part of a great golf swing. But how much is enough and what’s too much. I’ve tried using the concept of the chi line to describe just how much shift to the left there should be but that’s not good enough. So this month, let’s take a ride on the complexity train to understand how the weight shift occurs in the elite golf swings. But first, let me describe the most common way it is taught and performed by amateurs then let me give you two different ways that the elite golf swingers accomplish this.

If you’ve been told to:

- Shift your weight

- Post up on the left leg

- Finish on the left side

- Balance on your left foot at the finish of your swing

- Drive your right leg

- Hold the weight on the inside of your right leg at the top of the backswing

- Keep pressure on the inside of your right foot at the top of the backswing

Chances are you already do this wrong. The ambiguous instruction bites you by not being precise enough so most golfers will typically just exaggerate the shift to the left and be done with it.

How does this affect your anatomical movements?

Anatomically, the incorrect shift uses the power move of the right hip internal rotation and adduction in the early downswing phase whereas this should be part of the second firing. There are several problems with this. Once you use this movement, you can’t reuse it.

Another problem is that this typically comes along with left hip internal rotation and adduction as well. This is what I have termed “dual IR.” While this movement does promote a weight shift to the left, it is also restricting pelvic rotation due to the left leg fighting against the movements of the right. This would be like pedaling your bicycle while squeezing the hand brakes in a race with Lance Armstrong.

Yet golfers in dual IR know they can’t hit it from that position so they have to try to break out of dual IR jail. Here are two common methods of doing that.

Breaking out of Dual IR option 1 Slide’n Stall

One method would be to slide farther left. Instead of dual ADD which helps to create rotation, there is RH abduction and LH adduction.

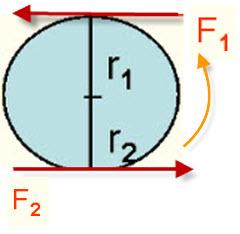

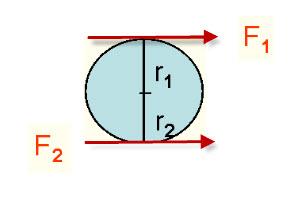

Remembering Force Couples

If we recall how force couples work, two parallel forces separated by perpendicular distance will produce rotation. In this diagram, F1 would be the left hip and F2 would be the right hip.

By doing the slide’n stall, both hips will move in the same direction thereby eliminating the force couple and therefore the rotation.

Also the left hip moves to external rotation (releasing the hand brake) way too late so while it may be better than holding IR the entire downswing, it isn’t optimal. The left knee typically must remain flexed or bent in order to continue sliding so this means losing another move of the elite where the left knee straightens at impact.

By sliding farther left, the golfer’s pelvis (and therefore sacrum) will move so far toward the target that the lower body can no longer rotate easily.

Simply put, lateral motion is inversely proportional to rotational motion.

Meanwhile, spine rotation slows to a crawl or a stall and the hands must take over the role of being the engine to the swing which usually leads to a flip.

Breaking out of Dual IR Option 2

Alternatively, if you combine right leg extension with left leg extension, it would become a jump/stall. In this scenario, the right hip also moves from adduction after transition to abduction at impact. This is reverse sequenced. Movements of the left side are limited as well. There is no ER and AB, just holding IR/ADD.

Either way, these two scenarios lead to lower hip rotation speeds and therefore less power.

How to shift your weight without going too far left or losing spine rotation

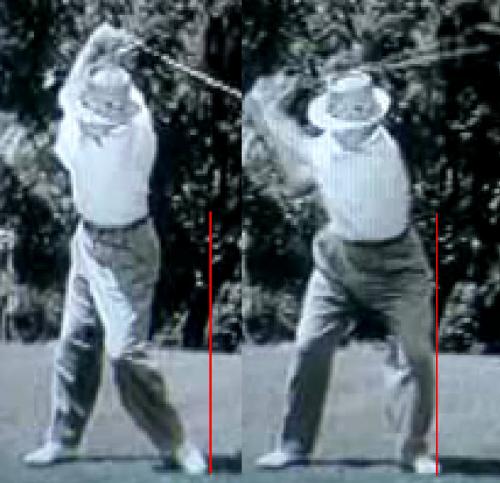

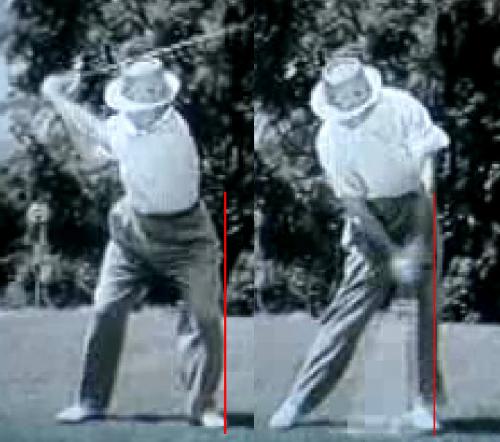

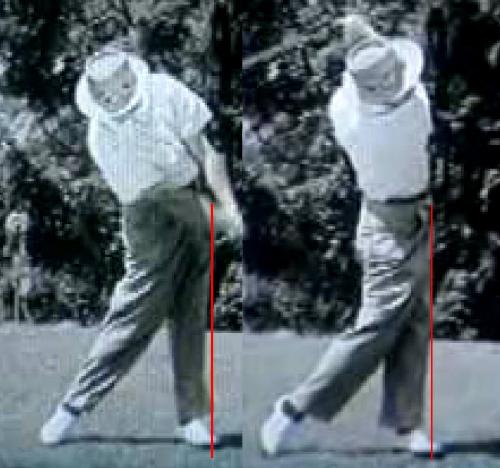

So how did Snead shift left?

There are two phases of weight shift occurring; one that starts in transition and another that starts just prior to impact. Anatomical movements of Snead’s right side are right hip ER, abduction and leg flexion. The left side uses left hip ER, abduction and a slight leg extension.

Snead’s second phase of the downswing uses dual IR, dual adduction and extension of the left leg (the right leg remains flexed as in picture on right).

The second phase of weight shift occurs starting just before impact as posterior pelvic tilt thrusts his lower spine and therefore weight toward the target.

But that isn’t everything there is. Perhaps using the high speed cameras we can see more movements.

New Micro Move: Left Pelvic Tilt (LPT)

Seen this for awhile but taking much time to understand fully before presenting the left pelvic tilt. Perhaps this micro move makes perfect logical sense. If the left hip needs to be moved up vertically (extension) and away from the target (adduction) before impact, there should be some stretch shorten cycle setting this off. Thus a counter movement in the opposite direction should be seen with the left hip moving down (hip flexion) and toward the target movement (abduction) should be seen in transition. Thus, LPT is responsible for the initial weight shift left.

The muscles primarily responsible for this movement would be iliopsoas muscles of the left side. This muscle action will flex the hip before extending. These muscles are the same ones use to bring your knees up in running or as I explain to little kids, playing musical chairs and needing to sit on a chair to the left of you. Thus it is a powerful movement in locomotion so it’s not as foreign as one might think.

Complexifying this situation more is that the gluteus maximus on the right side must be fired simultaneously in order to keep the right hip extended, abducted and externally rotated. Having both of these actions occur together is what creates the tilt of the hips toward the target.

Then milliseconds after the left pelvic tilt, the gluteus maximus fires on the left side creating the dual ER and AB that we see in the Snead squat.

Note: Lateral bend must be developed at the same time as LPT or your spine will tilt toward the target on the downswing!

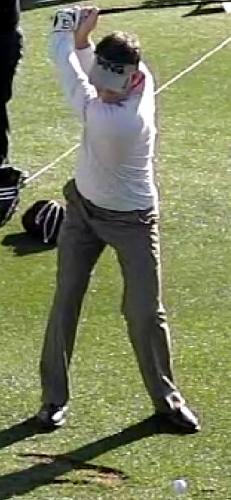

Since I’ve got great video of JB Holmes from all different angles, let’s see how this works in his swing.

From this angle, the swing does not appear to start from the “ground up.” The iliopsoas muscles are firing first to create the hip flexion and LPT. This starts the downswing motion.

JB’s squat move is a bit different than Snead’s. He achieves the dual ER/AB and knee separation but also uses right knee flexion/left knee extension to create a bit more pelvic rotation early in the downswing. Contrastingly, Snead had both knees in flexion at the end of squat move.

This is what it looks like from the two angles so you can clearly see how this helps the hip rotation.

This is what it looks like from normal front view.

Some pretty good players have this move.

Ben Hogan had it.

Here’s Bubba switched to a righty for easier understanding.

Jamie Sadlowski has this move.

Alvaro Quiros has it.

Tiger now seems to have lost it.

From the front view Tiger 2012 has lowered his right hip into flexion and early IR/ADD so he lost the LPT.

This is Tiger from 2010 US Open BF (before Foley). He still had the moves.

Here’s Troy Matteson. This looks different when looking from the back. He has more LPT at the top of the backswing and moves to a more right pelvic tilt in transition. Also, there is no dual ER/AB. This is dual IR/ADD at the start of the downswing.

Same move as Tiger? Adam’s attempt at copying Tiger has missed on some key dynamic moves. Looks prettier when the hips are level but it’s certainly not as dynamic.

Explaining dysfunction

If you aren’t doing this correctly in transition, perhaps the issues are with what instruction tends to lead you to. Firing off in ADD/IR at the start of the downswing will have you driving your right hip down and left hip up.

This makes the hips appear to be more level but it also leads you to slide too far left and stall.

LPT on Backswing

If you tilt the pelvis to the left too much on the backswing, what chance is there to do that move on the downswing? Wouldn’t you more likely have the left hip rise up in transition?

On the other hand, if the hips are more level and right hip/leg is in the proper position at the top of the backswing (RH ER/AB), LPT will automatically pull your weight to the left. You shouldn’t have to worry about shifting laterally.

Danger of Averages

Some biomechanical data shows that the average tour player’s pelvis is tilted about 6 degrees to the left on the backswing. Given that LPT on the backswing can lead to a missing micro move, would you really want to get anywhere near that average?

If you took the average of Woodland and Wilson, you might get the 6 degree tilt to the left. You can choose which side of the average you want to be on.

Another way to shift weight

This one is more of an illusion but since no one is paying close attention the “tricksters” will let you think they’ve shifted left when they really haven’t.

Scott Stallings looks like any other great golfer here. He’s shifted slightly toward the target in transition.

And he looks well balanced at the finish on his left side. But did his shift more left? Take a look at his left heel relative to the Farmer’s Insurance tee marker behind his left foot.

He uses the foot is faster than the eye technique to fool you into believing he’s sliding forward. Not correct you say?

Even the Great Tigerdini once used this sleight of foot to fool you into thinking he was shifting farther left.

Of course, you can always change to this and it is so different than in his prime. His entire body is shifted left.

For Left Loaders Only

For those that wish to load on the left side at the top of the backswing, you’re already there on the left, so why do you need to slide farther left? Perhaps the Arnold Palmer method of rotating from the start of the downswing might work better for you.

No Time Left for you (rotation)

Anyway, I hope this clears up some confusion of what’s really going on to shift your weight. I do not believe there is a way that you could consciously shift left, then stop shifting, then begin rotational movements in time to optimally hit a golf ball. This happens all in the space of about two tenths of a second and there’s no time to waste on purposeful sliding. The great players are just doing their moves to rotate as best they can while the weight/lateral shift occurs as a consequence of these correct moves.